Whether it be a gap yah adventure to save starving orphans in Africa or a two-week program teaching English in India during semester break, volunteer tourism (AKA voluntourism) is an increasingly common thing, especially among students. I was one of these students, having travelled to Ghana to help out at a radio station when I was in my second year of journalism – and I think these sorts of programs can be really good for all involved.

That being said, voluntourism is a controversial thing and people commonly attack the sustainability of the work done, the ethics of the companies sending volunteers abroad and the motives of the volunteers themselves. To be an ethical voluntourist, I think these three questions really do need to be asked.

Who are you travelling with?

I find it abhorrent that a company would use the developing world to pull our emotional heartstrings to make money – but they do. So don’t support them. In fact a study published in the Journal of Sustainable Tourism earlier this year reported irresponsible financial and ethical practices by many companies involved in volunteer tourism, such as the Cambodian orphanage-tourism crisis.

The study found that the more expensive companies were more likely to be dodgy. Its authors, Victoria Smith and Dr Xavier Font, both from Leeds Metropolitan University, told The Guardianthat a voluntourism company should be able to breakdown their program costs when asked (though they should do so anyway). So ask them, and get a solid answer. And not just a fluffy response like this one.

I went to Ghana with an American charity called Cosmic Volunteers. I’ll admit that at the time I probably didn’t know who I was travelling with enough; and I was very lucky in that Cosmic was ethical, extremely open about their work and weren’t making a profit. It could have just as easily gone the other way.

My six-week program cost me just over $1000 (though I think it’s gone up slightly), and covered my food and accommodation, airport transfers and a small wage for the country coordinator (a local girl who also hosted me, and let me crash two weeks for free). I find most organisations operate similar to this and cost anywhere between $1000 and $4000 for that amount of time. The highest range I’ve seen would be Antipodeans (who we’ve all seen spruik their stuff at schools and unis). Their month-long Build Africa program, by way of example, costs $3900. Honestly, I’ve never run my own voluntourism company and have no idea about some of the costs involved, so I’ve asked them for a breakdown of their costs and will post their response if they reply.

Is the work you’re doing actually helpful?

The problems faced by the developing world are extremely complex, and their solutions aren’t as simple as sending a group of western students to build shit – or else the problems would be solved. What’s lacking in these societies is a good system of government, which then in turn affects their education and public infrastructure. Projects filled with western students who build stuff or help out at orphanages potentially take work away from locals, and sometimes, don’t even cater for the needs of the community such as this village in Kenya, which had had three schools it didn’t particularly need built for it by western volunteers.

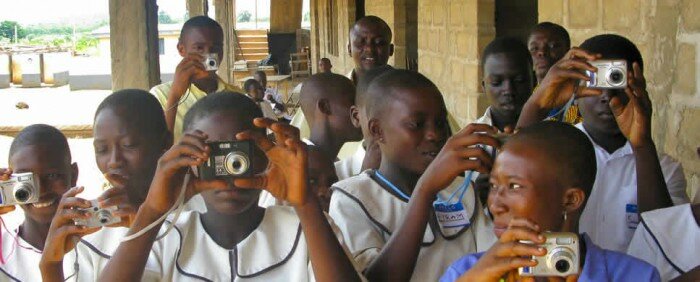

Better options would include volunteering with a specific skill that is lacking in these societies, which is generally more sought after by the better programs according to travel writer Martin Stevenson. To me, this means teaching new skills to contribute to a better future – my legacy in Ghana was establishing a social media arm of Pravda FM where I was placed (prior to that they hardly used it even though most Ghanaians had internet). I also recently met a doctor while in East Timor who was helping set up long-term research projects, which she believed to be far more beneficial than just working in a clinic.

This is not to say that all unskilled group travel projects are bad, it’s just really important that local dynamics and needs are accounted for. When I was travelling through the North of Ghana after my placement, I met a large group of British students who were on a two-week program, which saw them helping to build a library and helping at a local orphanage (this group of students were abhorrent, but I’ll get to that later). I later met the head of their NGO, Thrive Africa, who was a local man named Maxwell. He explained to me how his NGO interacted with local communities to figure out what sort of help they needed and where manpower was lacking (probably a given since he was from Ghana) – moreover the company was Ghanaian, so westerners aren’t profiteering from students trying to be ethical. I think it’s the responsibility of any volunteer to ask the company they go away with about the sustainability of projects, and whether or not they’ve dialogued with local communities. If they can’t provide a decent response, don’t go.

Why are you going?

Finally, I think people who go on these adventures to get a bunch of photos with little black kids are not only just awful, but also way too common. Heaps of people already feel this way about all voluntourism, as exampled in this ABC article. To me, it’s unrealistic to say that voluntourism doesn’t benefit the volunteer – but at the end of the day you’re there to help. I’m happy to accept that my time in Ghana worked to advance my career and taught me a shitload about being a versatile journalist, but I also like to think I made a tangible difference to the journalistic practice of the interns I was working with and overall benefitted my radio station – and tried to spend the bulk of my time over there concerning myself with how I could best help.

Oh and those students I was complaining about before? I met them when I was staying at Mole National Park to go on a safari. Many of them showed little respect for the local culture (we were in a Muslim area that frowned upon alcohol and they were drunk off their arses), and seemed more concerned with their own experience than the work they were doing (this was, however, only my first impression so who knows?). All hope was lost after I struck up a conversation with the prettiest girl in the group of 40 or so, who explained to me how excited she was to show her 100,000-strong group of Facebook followers all the photos of her with African kids (I later looked her up and unfortunately she wasn’t lying).

I accept that if someone does the right project with the right group but the wrong motives, they still help – they just look like a massive dick.

By Sam Caldwell.

This article was originally published on Hijacked.

No Comments